What Is A Pilgrimage Road

| Camino de Santiago | |

|---|---|

Map of the Way of St James in Europe | |

| Blazon | Pilgrims' mode |

| UNESCO Globe Heritage Site | |

| Official proper name | Routes of Santiago de Compostela: Camino Francés and Routes of Northern Spain |

| Criteria | Cultural: (2)(four)(six) |

| Reference | 669bis |

| Inscription | 1993 (17th Session) |

| Extensions | 2015 |

| Buffer zone | sixteen,286 ha (62.88 sq mi) |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official proper name | Routes of Santiago de Compostela in France |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii)(four)(vi) |

| Reference | 868 |

| Inscription | 1998 (22nd Session) |

| Area | 97.21 ha (0.3753 sq mi) |

The Camino de Santiago (Latin: Peregrinatio Compostellana, "Pilgrimage of Compostela"; Galician: O Camiño de Santiago),[1] known in English language as the Mode of St James, is a network of pilgrims' means or pilgrimages leading to the shrine of the apostle Saint James the Great in the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia in northwestern Spain, where tradition holds that the remains of the apostle are buried.

As Pope Bridegroom XVI said, "It is a fashion sown with so many demonstrations of fervour, repentance, hospitality, fine art and culture which speak to united states eloquently of the spiritual roots of the Old Continent."[2] Many follow its routes as a course of spiritual path or retreat for their spiritual growth. It is also popular with hiking and cycling enthusiasts and organized tour groups.

Created and established after the discovery of the relics of Saint James the Slap-up at the beginning of the 9th century, the Mode of St James became a major pilgrimage route of medieval Christianity from the 10th century onwards. Merely it was but after the capture of Granada in 1492, under the reign of Ferdinand Two of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, that Pope Alexander Six officially declared the Camino de Santiago to exist one of the "3 great pilgrimages of Christendom", along with Jerusalem and Rome.

In 1987, the Camino de Santiago, which encompasses several routes in Spain, France and Portugal, was declared the commencement Cultural Road of the Council of Europe. Since 2013, the Camino de Santiago has attracted more 200,000 pilgrims each year, with an annual growth rate of more than 10 percent. Pilgrims come mainly on foot and often from nearby cities, requiring several days of walking to reach Santiago. The French Way gathers two-thirds of the walkers, but other minor routes are experiencing a growth in popularity. The French Style and the routes in Espana were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, followed by the routes in France in 1998, because of their historical significance for Christianity as a major pilgrimage road and their testimony to the exchange of ideas and cultures across the routes.[3] [4]

Major Christian pilgrimage route [edit]

The Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela

The reliquary of Saint James in the Cathedral of Santiago

The Manner of St James was 1 of the most of import Christian pilgrimages during the later Middle Ages, and a pilgrimage route on which a plenary indulgence could be earned;[v] other major pilgrimage routes include the Via Francigena to Rome and the pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Fable holds that St James'south remains were carried by gunkhole from Jerusalem to northern Kingdom of spain, where he was buried in what is now the metropolis of Santiago de Compostela.[6]

Pilgrims on the Way tin can take i of dozens of pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela. Traditionally, equally with most pilgrimages, the Way of Saint James begins at 1's dwelling house and ends at the pilgrimage site. Even so, a few of the routes are considered main ones. During the Middle Ages, the road was highly travelled. Notwithstanding, the Black Decease, the Protestant Reformation, and political unrest in 16th century Europe led to its decline. Past the 1980s, only a few hundred pilgrims per year registered in the pilgrim's office in Santiago.[ commendation needed ]

Whenever St James's Day (25 July) falls on a Lord's day, the cathedral declares a Holy or Jubilee Twelvemonth. Depending on bound years, Holy Years occur in 5-, half-dozen-, and 11-year intervals. The most recent were 1993, 1999, 2004, 2010 and 2021. The next will exist 2027, and 2032.[vii]

History [edit]

Pre-Christian history [edit]

Roman span with 19 arches over the river Órbigo. The bridge has been integrated into the modern Camino Frances

The main pilgrimage route to Santiago follows an earlier Roman merchandise route, which continues to the Atlantic coast of Galicia, ending at Greatcoat Finisterre. Although it is known today that Cape Finisterre, Spain'south westernmost point, is not the westernmost point of Europe (Cabo da Roca in Portugal is farther west), the fact that the Romans chosen information technology Finisterrae (literally the stop of the earth or Land's End in Latin) indicates that they viewed information technology as such. At nighttime, the Galaxy overhead seems to signal the way, then the route acquired the nickname "Voie lactée" – the Milky Manner in French.[8]

Scallop symbol [edit]

St James'south shell, a symbol of the road, on a wall in León, Espana

A stylised scallop shell, the modern sign post of the Fashion

A marker indicating the route of the Way of St James

St James pilgrim accessories

The scallop crush, often constitute on the shores in Galicia, has long been the symbol of the Camino de Santiago. Over the centuries the scallop shell has taken on a variety of meanings, metaphorical, practical, and mythical, even if its relevance may have actually derived from the desire of pilgrims to take home a gift.

According to Spanish legends, Saint James had spent time preaching the gospel in Spain, but returned to Judaea upon seeing a vision of the Virgin Mary on the bank of the Ebro River.[9] [x] Two versions of the nigh common myth about the origin of the symbol concern the decease of Saint James, who was martyred by beheading in Jerusalem in 44 AD. They are:

-

- Version one: Afterwards James'southward death, his disciples shipped his body to the Iberian Peninsula to be buried in what is now Santiago. Off the coast of Spain, a heavy storm striking the transport, and the torso was lost to the sea. Subsequently some fourth dimension, however, it washed aground undamaged, covered in scallops.[ citation needed ]

- Version two: After James's martyrdom, his body was transported by a ship piloted by an angel, dorsum to the Iberian Peninsula to be buried in what is now Santiago. As the transport approached land, a nuptials was taking place on shore. The young groom was on horseback, and, upon seeing the ship's approach, his equus caballus got spooked, and horse and rider plunged into the sea. Through miraculous intervention, the horse and rider emerged from the water alive, covered in seashells.[xi] : 71

From its connection to the Camino, the scallop shell came to represent pilgrimage, both to a specific shrine as well as to heaven, recalling Hebrews 11:xiii, identifying that Christians "are pilgrims and strangers on the globe".[12] The scallop beat out is an ubiquitous sight along the Camino, where it often serves as a guide for pilgrims. The shell is even more commonly seen on the pilgrims themselves, who are thereby identified as pilgrims. Most pilgrims receive a shell at the start of their journey and display it throughout their journey.[13] During the medieval period, the shell was more a proof of completion than a symbol worn during the pilgrimage. The pilgrim's staff is a walking stick used by pilgrims on the manner to the shrine of Santiago de Compostela in Spain.[xiv] Generally, the stick has a hook so that something may exist hung from it; it may have a crosspiece.[xv] The usual form of representation is with a claw,[16] but in some the claw is absent.[17] The pilgrim'southward staff is represented under different forms and is referred to using dissimilar names, eastward.g. a pilgrim'due south crutch, a crutch-staff. The crutch, peradventure, should be represented with the transverse piece on the top of the staff (similar the letter "T") instead of across it.[18]

Medieval routes [edit]

Saint James with his pilgrim'southward staff. The chapeau is typical, but he often wears his emblem, the scallop beat, on the front brim of the hat or elsewhere on his clothes

Way of St James pilgrims (1568)

The primeval records of visits paid to the shrine at Santiago de Compostela date from the 9th century, in the time of the Kingdom of Asturias and Galicia. The pilgrimage to the shrine became the most renowned medieval pilgrimage, and it became customary for those who returned from Compostela to carry back with them a Galician scallop shell as proof of their completion of the journey. This practice gradually led to the scallop shell becoming the badge of a pilgrim.[19]

The earliest recorded pilgrims from beyond the Pyrenees visited the shrine in the heart of the 11th century, only information technology seems that it was not until a century later that large numbers of pilgrims from abroad were regularly journey in that location. The earliest records of pilgrims that arrived from England belong to the period between 1092 and 1105. However, by the early on 12th century the pilgrimage had become a highly organized affair.

One of the great proponents of the pilgrimage in the 12th century was Pope Callixtus II, who started the Compostelan Holy Years.[20]

The official guide in those times was the Codex Calixtinus. Published around 1140, the 5th book of the Codex is yet considered the definitive source for many modern guidebooks. Four pilgrimage routes listed in the Codex originate in French republic and converge at Puente la Reina. From at that place, a well-divers route crosses northern Spain, linking Burgos, Carrión de los Condes, Sahagún, León, Astorga, and Compostela.

Early 18th century facade of the San Marcos Monastery in Leon, which provided care for pilgrims over many centuries

The daily needs of pilgrims on their fashion to and from Compostela were met by a series of hospitals. Indeed, these institutions contributed to the development of the modernistic concept of 'infirmary'. Some Spanish towns still bear the name, such as Hospital de Órbigo. The hospitals were often staffed by Catholic orders and under purple protection. Donations were encouraged merely many poorer pilgrims had few wearing apparel and poor health often barely getting to the next infirmary.

Romanesque architecture, a new genre of ecclesiastical architecture, was designed with massive archways to cope with huge crowds of the devout.[21]

There was also the sale of the at present-familiar paraphernalia of tourism, such as badges and souvenirs. Pilgrims ofttimes prayed to Saint Roch whose numerous depictions with the Cross of St James tin can still exist seen along the Way even today.

The pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela was fabricated possible by the protection and liberty provided by the Kingdom of French republic, from which the majority of pilgrims originated. Enterprising French (including Gascons and other peoples not under the French crown) settled in towns along the pilgrimage routes, where their names announced in the archives. The pilgrims were tended by people similar Domingo de la Calzada, who was later recognized as a saint.

Pilgrims walked the Style of St James, oftentimes for months and occasionally years at a fourth dimension, to arrive at the great church in the main square of Compostela and pay homage to St James. Many arrived with very fiddling due to illness or robbery or both. Traditionally pilgrims lay their hands on the pillar merely within the doorway of the cathedral, and so many now have done this information technology has visibly worn away the stone.[22]

The popular Castilian name for the astronomical Milky way is El Camino de Santiago. Co-ordinate to a common medieval legend, the Milky way was formed from the dust raised by travelling pilgrims.[23]

Another legend states that when a hermit saw a bright star shining over a hillside near San Fiz de Solovio, he informed the bishop of Iria Flavia, who institute a grave at the site with three bodies inside, i of which, he asserted, was that of St James. Subsequently, the location was called "the field of the star" (Campus Stellae, corrupted to "Compostela").[24]

Some other origin myth mentioned in Book Four of the Book of Saint James relates how the saint appeared in a dream to Charlemagne, urging him to liberate his tomb from the Moors and showing him the direction to follow past the road of the Galaxy.[ commendation needed ]

Pilgrimage as penance [edit]

The Church employed (and employs) rituals (the sacrament of confession) that can atomic number 82 to the imposition by a priest of penance, through which the sinner atones for his or her sins. Pilgrimages were deemed to exist a suitable grade of expiation for sin and long pilgrimages would exist imposed as penance for very serious sins. Every bit noted in the Catholic Encyclopedia:

In the registers of the Inquisition at Carcassone...we find the four following places noted as beingness the centres of the greater pilgrimages to exist imposed as penances for the graver crimes: the tomb of the Apostles at Rome, the shrine of St. James at Compostella [sic], St. Thomas' trunk at Canterbury, and the relics of the Iii Kings at Cologne.

Pilgrimages could also be imposed equally judicial punishment for criminal offence, a do that is still occasionally used today. For instance, a tradition in Flanders persists of pardoning and releasing one prisoner every yr[25] under the condition that, accompanied by a guard, the prisoner walks to Santiago wearing a heavy backpack.

Enlightenment era [edit]

During the American Revolution, John Adams (who would become the second President of the United States) was ordered by Congress to become to Paris to obtain funds for the crusade. His ship started leaking and he disembarked with his two sons at Finisterre in 1779. From there, he proceeded to follow the Way of St James in the reverse direction of the pilgrims' route, in order to become to Paris overland. He did not stop to visit Santiago, which he afterward regretted. In his autobiography, Adams described the community and lodgings afforded to St James's pilgrims in the 18th century and he recounted the legend as it was told to him:[26]

I have always regretted that We could not notice fourth dimension to brand a Pilgrimage to Saintiago de Compostella. We were informed ... that the Original of this Shrine and Temple of St. Iago was this. A certain Shepherd saw a bright Light in that location in the night. Afterwards it was revealed to an Archbishop that St. James was buried there. This laid the Foundation of a Church, and they have congenital an Altar on the Spot where the Shepherd saw the Calorie-free. In the time of the Moors, the People fabricated a Vow, that if the Moors should exist driven from this Country, they would give a certain portion of the Income of their Lands to Saint James. The Moors were defeated and expelled and information technology was reported and believed, that Saint James was in the Boxing and fought with a drawn Sword at the head of the Spanish Troops, on Horseback. The People, believing that they owed the Victory to the Saint, very cheerfully fulfilled their Vows by paying the Tribute. ... Upon the Supposition that this is the identify of the Sepulchre of Saint James, there are great numbers of Pilgrims, who visit it, every Yr, from French republic, Spain, Italian republic and other parts of Europe, many of them on foot.

Modern-day pilgrimage [edit]

A Camino milestone by St Leonard'south church, Wojnicz, Poland

Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port

A boardwalk on the Portuguese coastal Way: Coastal sand dunes of Póvoa de Varzim

Although it is commonly believed that the pilgrimage to Santiago has connected without break since the Middle Ages, few modern pilgrimages antedate the 1957 publication of Irish Hispanist and traveler Walter Starkie'south The Route to Santiago.[11] The revival of the pilgrimage was supported by the Spanish government of Francisco Franco, much inclined to promote Spain's Cosmic history. "It has been but recently (1990s) that the pilgrimage to Santiago regained the popularity information technology had in the Eye Ages."[27]

Since then, hundreds of thousands (over 300,000 in 2017)[28] of Christian pilgrims and many others fix out each year from their homes, or from popular starting points across Europe, to make their way to Santiago de Compostela. Most travel by pes, some by bicycle, and some even travel as their medieval counterparts did, on horseback or by donkey. In addition to those undertaking a religious pilgrimage, many are hikers who walk the route for travel or sport. Also, many consider the experience a spiritual retreat from modern life.[29]

Routes [edit]

Here, only a few routes are named. For a complete list of all the routes (traditional and less so), come across: Camino de Santiago (route descriptions).

The Camino Francés, or French Fashion, is the most popular. The Via Regia is the last portion of the (Camino Francés).[ citation needed ] Historically, because of the Codex Calixtinus, most pilgrims came from France: typically from Arles, Le Puy, Paris, and Vézelay; some from Saint Gilles. Cluny, site of the celebrated medieval abbey, was another important rallying point for pilgrims and, in 2002, it was integrated into the official European pilgrimage road linking Vézelay and Le Puy.

About Spanish consider the French border in the Pyrenees the natural starting bespeak. By far the near common, modernistic starting point on the Camino Francés is Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, on the French side of the Pyrenees, with Roncesvalles on the Spanish side also being popular.[xxx] The distance from Roncesvalles to Santiago de Compostela through León is nigh 800 km (500 mi).

The Camino Primitivo, or Original Style, is the oldest route to Santiago de Compostela, first taken in the 9th century, which begins in Oviedo.[31] Camino Portugués, or the Portuguese Way, is the second-most-popular route,[30] starting at the cathedral in Lisbon (for a total of nearly 610 km) or at the cathedral in Porto in the north of Portugal (for a full of about 227 km), and crossing into Galicia at Valença.[32]

The Camino del Norte, or the Northern Style, is also less traveled and starts in the Basque metropolis of Irun on the border with French republic, or sometimes in San Sebastián. It is a less popular road because of its changes in elevation, whereas the Camino Frances is mostly flat. The route follows the coast along the Bay of Biscay until it nears Santiago. Though information technology does not pass through as many historic points of interest as the Camino Frances, it has cooler summer weather condition. The route is believed to have been first used by pilgrims to avoid traveling through the territories occupied past the Muslims in the Middle Ages.[33]

The Central European camino was revived after the Autumn of the Berlin Wall. Medieval routes, Camino Baltico and the Via Regia in Poland pass through nowadays-mean solar day Poland accomplish equally far northward equally the Baltic states, taking in Vilnius, and Eastwards to nowadays-day Ukraine and take in Lviv, Sandomierz and Kraków.[34]

Adaptation [edit]

Monastery of San Xuliàn de Samos, which provides shelter for pilgrims

In Spain, France, and Portugal, pilgrims' hostels with beds in dormitories provide overnight accommodation for pilgrims who hold a credencial (see below). In Spain this type of accommodation is called a refugio or albergue, both of which are like to youth hostels or hostelries in the French system of gîtes d'étape.

Hostels may exist run by a local parish, the local council, private owners, or pilgrims' associations. Occasionally, these refugios are located in monasteries, such as the 1 in the Monastery of San Xulián de Samos that is run by monks, and the one in Santiago de Compostela.

The terminal hostel on the route is the famous Hostal de los Reyes Católicos, which lies in the Praza do Obradoiro beyond the Cathedral. Information technology was originally constructed as hospice and hospital for pilgrims by Queen Isabella I of Castile and Male monarch Ferdinand Ii of Aragon, the Catholic Monarchs. Today it is a luxury five-star Parador hotel, which nonetheless provides gratis services to a express number of pilgrims daily.

Credencial or pilgrim's passport [edit]

St. James pilgrim passport stamps in Spain for the Camino Frances

Nigh pilgrims buy and carry a certificate called the credencial,[35] which gives access to overnight accommodation along the route. Likewise known as the "pilgrim's passport", the credencial is stamped with the official St. James stamp of each boondocks or refugio at which the pilgrim has stayed. Information technology provides pilgrims with a record of where they ate or slept and serves as proof to the Pilgrim's Office in Santiago that the journey was achieved according to an official route and thus that the pilgrim qualifies to receive a compostela (certificate of completion of the pilgrimage).

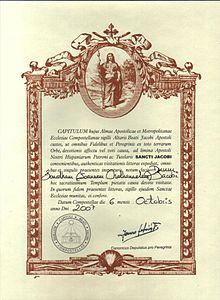

Compostela [edit]

The compostela is a certificate of accomplishment given to pilgrims on completing the Way. To earn the compostela one needs to walk a minimum of 100 km or bike at least 200 km. In practice, for walkers, the closest convenient betoken to commencement is Sarria, equally it has good bus and rails connections to other places in Spain. Pilgrims arriving in Santiago de Compostela who have walked at least the last 100 km (62 mi), or cycled 200 km (120 mi) to get there (equally indicated on their credencial), and who land that their motivation was at to the lowest degree partially religious, are eligible for the compostela from the Pilgrim's Office in Santiago.[36]

The compostela has been indulgenced since the Early on Centre Ages and remains so to this day, during Holy Years.[37] The English language translation reads:

The CHAPTER of this holy churchly and metropolitan Church of Compostela, guardian of the seal of the Chantry of the blessed Apostle James, in order that it may provide accurate certificates of visitation to all the true-blue and to pilgrims from all over the earth who come with devout amore or for the sake of a vow to the shrine of our Apostle St. James, the patron and protector of Spain, hereby makes known to each and all who shall inspect this nowadays certificate that [Name]

has visited this most sacred temple for the sake of pious devotion. As a faithful witness of these things I confer upon him [or her] the present certificate, authenticated past the seal of the aforementioned Holy Church.

Given at Compostela on the [mean solar day] of the calendar month of [month] in the year of the Lord [year].

Deputy Canon for Pilgrims

The simpler document of completion in Castilian for those with not-religious motivation reads:

La South.A.Thousand.I. Catedral de Santiago de Compostela le expresa su bienvenida cordial a la Tumba Apostólica de Santiago el Mayor; y desea que el Santo Apóstol le conceda, con abundancia, las gracias de la Peregrinación.

English translation:

The Holy Apostolic Metropolitan Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela expresses its warm welcome to the Tomb of the Campaigner St. James the Greater; and wishes that the holy Apostle may grant you, in abundance, the graces of the Pilgrimage.

The Pilgrim's Part gives more than than 100,000 compostelas each year to pilgrims from more 100 countries. Yet, the requirements to earn a compostela ensure that non anybody who walks on the Camino receives 1. The requirements for receiving a compostela are: ane) make the Pilgrimage for religious/spiritual reasons or at least have an mental attitude of search, 2) do the concluding 100 km on foot or horseback or the final 200 km by wheel. 3) collect a sure number of stamps on a credencial.[38]

Pilgrim's Mass [edit]

| Green confined are holy years |

A Pilgrim's Mass is held in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela each solar day at 12:00 and 19:30.[39] Pilgrims who received the compostela the 24-hour interval before have their countries of origin and the starting signal of their pilgrimage announced at the Mass. The Botafumeiro, one of the largest censers in the earth, is operated during certain Solemnities and on every Friday, except Good Friday, at 19:30.[40] Priests administer the Sacrament of Penance, or confession, in many languages. In the Holy Year of 2010 the Pilgrim's Mass was exceptionally held four times a mean solar day, at ten:00, 12:00, xviii:00, and nineteen:30, catering for the greater number of pilgrims arriving in the Holy Year.[41]

Pilgrimage equally tourism [edit]

The Xunta de Galicia (Galicia's regional regime) promotes the Mode equally a tourist activity, especially in Holy Compostela Years (when 25 July falls on a Sunday). Following Galicia'southward investment and advertising entrada for the Holy Yr of 1993, the number of pilgrims completing the route has been steadily ascent. The most recent Holy Year occurred in 2021, 11 years after the last Holy Twelvemonth of 2010. More than than 272,000 pilgrims made the trip during the class of 2010. The adjacent Holy Year pilgrimage will occur in 2027.

| Year | Pilgrims |

|---|---|

| 2021 | 178,9121 |

| 2020 | 54,144 |

| 2019 | 347,578 |

| 2018 | 327,378 |

| 2017 | 301,036 |

| 2016 | 277,915 |

| 2015 | 262,458 |

| 2014 | 237,886 |

| 2013 | 215,880 |

| 2012 | 192,488 |

| 2011 | 179,919 |

| 2010 | 272,703 1 |

| 2009 | 145,877 |

| 2008 | 125,141 |

| 2007 | 114,026 |

| 2006 | 100,377 |

| 2005 | 93,924 |

| 2004 | 179,944 i |

| 2003 | 74,614 |

| 2002 | 68,952 |

| 2001 | 61,418 |

| 2000 | 55,004³ |

| 1999 | 154,613 i |

| 1998 | xxx,126 |

| 1997 | 25,179 |

| 1996 | 23,218 |

| 1995 | 19,821 |

| 1994 | xv,863 |

| 1993 | 99,436 one |

| 1992 | ix,764 |

| 1991 | seven,274 |

| 1990 | 4,918 |

| 1989 | 5,760² |

| 1988 | 3,501 |

| 1987 | 2,905 |

| 1986 | i,801 |

| 1985 | 690 |

| 1 Holy Years (Xacobeo/Jacobeo) 2 4th World Youth Twenty-four hour period in Santiago de Compostela 3 Santiago named European Capital of Culture Source: The athenaeum of Santiago de Compostela. [42] [43] [44] [45] | |

In moving picture and boob tube [edit]

(Chronological)

- The pilgrimage is central to the plot of the film The Milky Fashion (1969), directed past surrealist Luis Buñuel. Information technology is intended to critique the Catholic church building, as the modern pilgrims see various manifestations of Catholic dogma and heresy.

- The Naked Pilgrim (2003) documents the journey of art critic and journalist Brian Sewell to Santiago de Compostela for the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland's Channel Five. Travelling by automobile along the French route, he visited many towns and cities on the manner including Paris, Chartres, Roncesvalles, Burgos, León and Frómista. Sewell, a lapsed Catholic, was moved by the stories of other pilgrims and by the sights he saw. The series climaxed with Sewell's emotional response to the Mass at Compostela.

- The Manner of St. James was the key feature of the film Saint Jacques... La Mecque (2005) directed past Coline Serreau.

- In The Way (2010), written and directed by Emilio Estevez, Martin Sheen learns that his son (Estevez) has died early on along the route and takes upwardly the pilgrimage in order to complete it on the son'south behalf. The film was presented at the Toronto International Moving picture Festival in September 2010[46] [47] and premiered in Santiago in November 2010.

- On his PBS travel Europe tv set series, Rick Steves covers Northern Kingdom of spain and the Camino de Santiago in serial 6.[48]

- In 2013, Simon Reeve presented the "Pilgrimage" serial on BBC2, in which he followed various pilgrimage routes beyond Europe, including the Camino de Santiago in episode 2.[49]

- In 2014, Lydia B Smith[50] and Time to come Educational Films released Walking the Camino: Vi Means to Santiago [51] in theatres across the U.S. and Canada. The film features the accounts and perspectives of six pilgrims as they navigate their respective journeys from France to Santiago de Compostela. In 2015, it was distributed across the Earth, playing theatres throughout Europe, Commonwealth of australia, and New Zealand. It recently aired on NPTV and continues to be featured in festivals relating to the Spirituality, Mind Body, Travel, and Adventure.

- In 2018, series one of BBC 2'southward Pilgrimage followed this pilgrimage.

Gallery [edit]

-

Monument to pilgrims in Burgos

-

A pilgrims hostel in Mansilla de las Mulas

-

A pilgrim on the barren and impressive meseta, which offers a long and challenging walk

-

A pilgrim near San Juan de Ortega

-

View on el Camino del Norte. San Sebastián, playa de la Concha

-

Sea view on el Camino del Norte, budgeted Onton

-

A pilgrim along the northern route of the Camino de Santiago

Selected literature [edit]

(Alphabetical by author's surname)

- Boers, Arthur Paul (2007). The Way Is Made by Walking: A Pilgrimage Along the Camino de Santiago. InterVarsity Press. ISBN978-0-8308-3507-2.

- Brown, Kim (2013). Spiritual Lessons along the Camino. Imprimatur by Primal DiNardo. ISBN978-0615816661.

- Capil, Apr (2018). Camino de Limon: 47 Days on The Way of St. James. ISBN978-1720857136.

- Carson, Anne (1987). Kinds of Water.

- Coelho, Paulo (1987). The Pilgrimage.

- Donlevy, Simon (2020). There's Something Going On! Walking the Camino de Santiago. The Choir Press. ISBN978-i-78963-158-6.

- Hemingway, Ernest (1926). The Sun Also Rises.

- Hitt, Jack (1994). Off the Road: A Modern-Day Walk Down the Pilgrim's Route into Espana.

- Kerkeling, Hape (2009). I'grand Off Then: Losing and Finding Myself on the Camino de Santiago.

- Order, David (1995). Therapy.

- MacLaine, Shirley (2001). The Camino: A Journeying of the Spirit.

- Michener, James (1968). Iberia.

- Moore, Tim (2004). Spanish Steps: Travels With My Donkey.

- Nooteboom, Cees (1996). Roads to Santiago.

- Pivonka, T.O.R., Fr. Dave (2009). Hiking the Camino: 500 Miles With Jesus. Franciscan Media. ISBN978-0867168822.

- Rudolph, Conrad (2004). Pilgrimage to the End of the Earth: The Route to Santiago de Compostela.

- Simsion, Graeme; Buist, Anne (2017). Two Steps Forwards.

- Starkie, Walter (1957). The Route to Santiago. E. P. Dutton & Company, Inc.

- Whyte, David (1 May 2012). Santiago. Pilgrim. Many Rivers Press. p. [1]. ISBN978-1932887259.

Come across also [edit]

- Camino de Santiago (route descriptions)

- Codex Calixtinus

- Confraternity of Saint James

- Cross of Saint James

- Dominic de la Calzada

- Hajj

- Japan 100 Kannon Pilgrimage

- Kumano Kodo

- Mary Remnant

- Order of Santiago

- Palatine Ways of St. James

- Path of Miracles

- Shikoku Pilgrimage

- Via Jacobi

- Walking the Camino: Six Means to Santiago

- World Heritage Sites of the Routes of Santiago de Compostela in French republic

References [edit]

- ^ In other languages: Spanish: El Camino de Santiago; Portuguese: O Caminho de Santiago; French: Le chemin de Saint-Jacques; German: Der Jakobsweg; Italian: Il Cammino di san Giacomo.

- ^ "Bulletin to the Archbishop of Santiago de Compostela (Spain) on the occasion of the opening of the Compostela Holy Year 2010 (December nineteen, 2009) | BENEDICT XVI". www.vatican.va . Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "Routes of Santiago de Compostela: Camino Francés and Routes of Northern Espana". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Routes of Santiago de Compostela in France". UNESCO World Heritage Middle. Un Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Arrangement. Retrieved 4 Nov 2021.

- ^ Kent, William H. (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Cosmic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. This entry on indulgences suggests that the development of the doctrine came to include a pilgrimage to shrines as a trend that developed from the eighth century A.D.: "Among other forms of substitution were pilgrimages to well-known shrines such as that at St. Albans in England or at Compostela in Spain. But the most important place of pilgrimage was Rome. According to Bede (674–735) the visitatio liminum, or visit to the tomb of the Apostles, was fifty-fifty then regarded as a proficient work of slap-up efficacy (Hist. Eccl., IV, 23). At start the pilgrims came just to venerate the relics of the Apostles and martyrs, just in class of time their main purpose was to gain the indulgences granted past the pope and fastened especially to the Stations."

- ^ "Santiago de Compostela | Spain". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved xvi February 2021.

- ^ "Holy Years at Santiago de Compostela". Archived from the original on 16 September 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Medieval footpath under the stars of the Milky way Archived 17 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine". Telegraph Online.

- ^ Chadwick, Henry (1976), Priscillian of Avila, Oxford University Press

- ^ Fletcher, Richard A. (1984), Saint James'south Catapult : The Life and Times of Diego Gelmírez of Santiago de Compostela, Oxford University Press

- ^ a b Starkie, Walter (1965) [1957]. The Roads to Santiago: Pilgrims of St. James. University of California Press.

- ^ Kosloski, Philip (25 July 2017). "How the scallop beat became a symbol of pilgrimage".

- ^ "Camino de Santiago en Navarra". Regime of Navarre. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Pilgrim's or Palmer'southward Staff French: bourdon: this was used as a device in a coat of arms as early at to the lowest degree every bit Edward II's reign, as volition exist seen. The Staff and the Escallop shell were the bluecoat of the pilgrim, and hence information technology is but natural information technology should find its manner into the shields of those who had visited the Holy Land.

- ^ "figure one". heraldsnet.org.

- ^ "figure ii". heraldsnet.org.

- ^ "J". A GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN HERALDRY.

- ^ Waldron, Thomas (1979). "The Sign of the Scallop Beat out". The Furrow. 30 (10): 646–649. JSTOR 27660823.

- ^ "Brief history: The Camino – past, nowadays & future". Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved half-dozen March 2014.

- ^ "Romanesque Architecture - Durham Earth Heritage Site". www.durhamworldheritagesite.com.

- ^ Davies, Bethan; Cole, Ben (2003). Walking the Camino de Santiago. Pili Pala Press. p. 179. ISBN0-9731698-0-X.

- ^ Bignami, Giovanni F. (26 March 2004). "Visions of the Milky way". Science. 303 (5666): 1979. doi:10.1126/science.1096275. JSTOR 3836327. S2CID 191291730.

- ^ Aruna Vasadevan (5 Nov 2013). "Santiago de Compostela (La Coruña, Spain)". In Trudy Band; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (eds.). Southern Europe: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Taylor & Francis. pp. 621–624. ISBN978-1-134-25965-6.

- ^ "Huellas españolas en Flandes". Turismo de Bélgica. Archived from the original on 1 Apr 2012.

- ^ "John Adams autobiography, part 3, Peace, 1779–1780, sheet x of 18". Harvard Academy Printing, 1961. Baronial 2007.

- ^ Mitchell-Lanham, Jean (2015). The Lore of the Camino de Santiago: A Literary Pilgrimage. Two Harbors Press. p. 15. ISBN978-i-63413-333-3.

- ^ Erimatica. "Estadística de peregrinos del Camino de Santiago a 2018". Camino de Santiago. Guía definitiva: etapas, albergues, rutas (in European Spanish). Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "The present-day pilgrimage". The Confraternity of Saint James. Archived from the original on fifteen July 2006.

- ^ a b "Informe estadístico Año 2016" (PDF). Oficina del Peregrino de Santiago de Compostela. Retrieved eighteen September 2017.

- ^ "Primitive Way-Camino de Santiago Primitivo". Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ The Confraternity of Saint James. "The Camino Portugués". Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "Camino del Norte". Camino Means.

- ^ Camino Polaco. Teologia - Sztuka - Historia - Teraźniejszość - Edited by Fr. dr. Piotr Roszak and professor dr. Waldemar Rozynkowski. published by Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika (Toruń); book 1 (2014), book ii (2015), volume 3 (2016) in Smooth.

- ^ Barry Smith, Olimpia Giuliana Loddo and Giuseppe Lorini, "On Credentials", Journal of Social Ontology, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/jso-2019-0034 | Published online: 07 Aug 2020.

- ^ "▷ The Compostela . What is it. How to get information technology. Minimum distance required". Pilgrim . Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "The Compostela". Confraternity of Saint James. Archived from the original on 29 Jan 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ^ "The Compostela". Oficina del Peregrino de Santiago de Compostela.

- ^ "Masses Hours". catedraldesantiago.es. Catedral de Santiago de Compostela. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved six August 2016.

- ^ "The Botafumeiro". catedraldesantiago.es. Catedral de Santiago de Compostela. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ^ "The Holy Year: When Does the Holy Year Take Place?". catedraldesantiago.es. Catedral de Santiago de Compostela. Archived from the original on xvi August 2016. Retrieved six August 2016.

It is Holy Year in Compostela when the 25th of July, Commemoration of the Martyrdom of Saint James, falls on a Sunday.

eight December 2015 – 20 November 2016, Pope Francis's Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy, was also a Holy Year. - ^ "Pilgrims by year according to the office of pilgrims at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela". Archived from the original on ane January 2010.

- ^ "Pilgrims 2006–2009 co-ordinate to the role of pilgrims at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela". Archived from the original on 19 January 2012.

- ^ "Statistics". Archived from the original on xiv August 2014.

- ^ "Statistics". Oficina del Peregrino de Santiago de Compostela.

- ^ "The Mode (2010)". IMDb. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ "The fashion official pic site". Theway-themovie.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ "Rick Steves travel evidence, episode: "Northern Spain and the Camino de Santiago"". ricksteves.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ "YouTube". YouTube. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014.

- ^ "Lydia B Smith". IMDb. Retrieved 25 Nov 2019.

- ^ "Walking the Camino: Six Ways to Santiago".

External links [edit]

- "The Art of medieval Spain, A.D. 500–1200, an exhibition catalog". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries. pp. 175–183.

(fully available online as PDF), which contains fabric on Way of St. James

What Is A Pilgrimage Road,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camino_de_Santiago

Posted by: alleynemage2002.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is A Pilgrimage Road"

Post a Comment